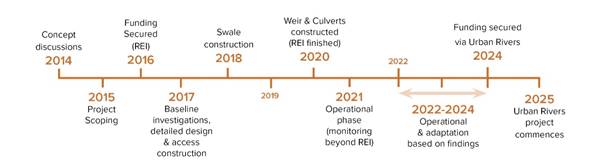

The Peel Main Drain (PMD) and Swale “off-line treatment” Project commenced in 2015, focusing on water quality in the Serpentine Wetlands and where and how to install a set of Swales to treat the flow in PMD to reduce phosphorous concentrations. The investigation, design, approvals and construction were completed in 2021 and the system has now been operating for the past four years with significant learnings that were reported in the last Wattle&Quoll.

In June 2023, the Serpentine Wetlands (as shown in Figure 1, and located in both the north and south of the project area) were again reviewed, but this time including the hydrology of the area as well as water quality. The 2023 study initially looked at the southern wetlands near the outlet culvert, but in February 2024 was extended to all of the Serpentine Wetlands of the PMD area. All the initial work on the Swales and Serpentine Wetlands was funded by the Regional Estuaries Initiative (REI) Project (in 2015) and the Water Corporation and was extended using PHCC’s own funding.

The preliminary monitoring in 2023-24 gave PHCC a far better understanding of how the Wetlands were behaving both hydrologically and allowed determination of their ecological health from the water quality. It also allowed PHCC to successfully put in for Commonwealth Funding to restore the wetlands and the neighbouring Serpentine River to healthy ecosystems. This is the project that is receiving funding under the Australian Government’s Urban Rivers and Catchments Program (URCP).

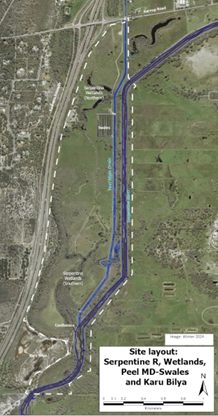

The area of land where the restoration work is being undertaken is shown in Figure 1, and is bounded by Peel Main Drain and Serpentine River, Karnup Road, Kwinana Freeway and Karu Bilya.

This document undertakes a preliminary analysis of the behaviour of the Southern Wetland System of the Serpentine Wetlands.

Recent History since European Settlement

European settlement of the area occurred in the 1830’s and by the early 1900’s agriculture was found to be extremely difficult with 30% of years receiving more that 1000mm of rainfall (much greater than the recent annual average (2000 – 2025) of 734 mm recorded at DWER’s Dog Hill rain gauge nearby), and causing extensive inundation of the land for six months of the year.

The agriculture sector lobbied the State Government to provide flood relief and drain “their” land. This works program was undertaken in the 1920’s after a series of very wet years from 1904 to 1917 (5 years in excess of 1100mm, followed by 3 more in the 1920’s).

What was constructed was a drainage network that extended from Cockburn and Armadale down to the land that PHCC are attempting to restore near Karu Bilya and converted many wetlands and rivers into the trapezoidal drains of Birriga Main Drain, Serpentine Drain and PMD. This network of channels drained on average 80GL of water per annum from the catchment in the 1980’s & 1990’s and since 2000, is currently draining ~35GL/a out into the Estuary. The negative side-effect is that it has also been draining large loads of nutrients to the Estuary.

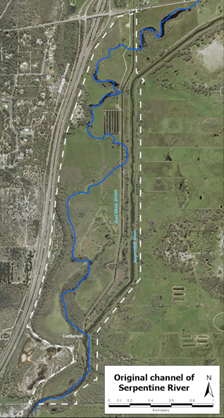

The constructed drainage network completely changed the behaviour of the Serpentine River, separating the original channel and its floodplain from the drainage system. The original meandering river channel is shown in Figure 2. What remained in this area were the Serpentine Wetlands which had their own catchment area which was completely separate from the Main Drains of Peel and Serpentine. And within the Serpentine Wetland sub-catchment, even the wetlands contain drainage with shallow drains flowing from north to south and encouraging flow out of the sub-catchment into Peel MD through a culvert just near its confluence with the Serpentine Drain.

The Northern section of wetlands has a catchment area of 38ha while the Southern section is 100ha. Groundwater levels in the Serpentine Wetlands are shallow ranging from 1.6m below ground level in the North at the end of autumn through to 0.4m above the surface in the South in early Spring where the whole floodplain is inundated for a week or two each year. This means that just the rainfall in the sub-catchment easily wets the catchment and its wetlands and briefly inundates the southern end of the wetlands before quickly discharging through the outlet culvert near the confluence.

Rainfall

Average rainfall in the catchment has significantly varied since BoM records commenced at the start of last century (Serpentine Town [009039]):

- Average from 1904 – 1967 =980mm/a;

- Average from 1968 – 2000 = 828mm/a;

- Average from 2001 – 2025 = 717mm/a.

Even more important to the Serpentine Wetland ecosystem are the June to September rainfalls in the local catchment where the winter rainfall in the past 3 years has been:

- 2023 = 481mm

- 2024 = 525mm

- 2025 = 620mm

Note: the 620mm this 2025 winter is the highest winter rainfall here since 1999 (640mm) and compares to the average winter rainfall for these months since 2001 of 480mm.

Inundation

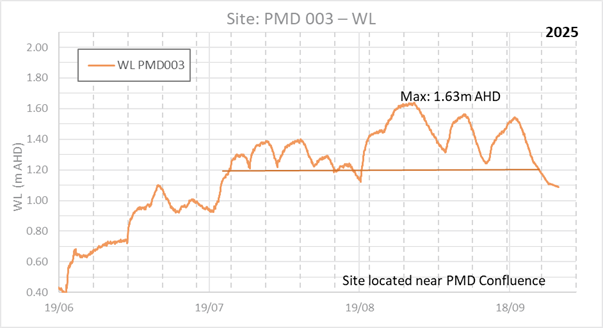

The water level peak in the wetlands this year was slightly higher than it had been on either of the previous two years of water level data that PHCC have collected (approx., 0.1m higher). During 2025, water levels were above 1.2m AHD for a period of 9 weeks while in 2024 it was 7 weeks and 2023 only 4 weeks. An example of the inundation is shown in Figure 3, however, due to the efficiency of drainage, this same area is very dry for over 10 months of the year.

Figure 3 – Inundation of TEC at site PMD005-006 [Peel#03] (26-08-2025)

Inundation is not sustained; as soon as the water level in the Southern Wetland is above about 1.2m AHD, the drainage system “kicks in” with water quickly discharging out of the culvert at the base of the wetland system and out into Peel MD as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – Culvert outlet to Peel MD discharging at ~250L/s (WL=1.45m) (02/09/2025)

To understand the behaviour of the Serpentine Wetlands, analysis was undertaken using Landgate’s 2022 LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) topography to determine the water level versus waterbody volume relationship.

Analysis of the water level data during 2025 shows that there were five significant water level peaks in the range of 1.39m to 1.64m AHD (see Figure 5). In each case the water level fell quickly afterwards over a period of between 2 and 9 days and a calculated discharge volume through the culvert during each of the five events of between 48ML to 136ML. The total loss of water through the drainage system for those five events was 492ML; 2.4-times the volume of the Southern wetland when full (210ML).

The inundation extent was similar in both 2023 and 2024, although the rainfall and water volumes were not quite as great. Total discharge through the culvert during the three significant events in those years was 200ML in 2023 and 230ML in 2024. This meant that the drainage system ensured that the wetland water levels were below 1.20m by mid-September in 2024 and 2025, and late-August in 2023. They dry out quickly by evaporation during the Spring-Summer-Autumn and do not return to the 1.2m water level again until late July; 10½ months later.

Figure 5 – Water levels in Southern Wetlands

In summary, when the water level in the wetland is at 1.60m AHD, the wetland contains a volume of 210ML (see Figure 6 for inundation). At 1.2m AHD (Figure 7), the volume is only 70ML, a loss of 140ML. This loss is what the culvert & drainage system can discharge in only 7-9 days.

Water Quality

Throughout the 2024 and 2025 summer, PHCC have been also collecting physical water quality, Total Nitrogen (TN) and Total Phosphorous (TP) samples at many of the wetland sites. These were sites that were set-up at the beginning of the project in 2016-2018, but monitoring was recommenced recently. At the sites drying out in Feb-Mar, the salinity was about half that of seawater, while the TN concentrations were in the ‘Extreme’ Classification and TP was classed as ‘Very High’. Back in the 2016-18 monitoring, the TN and TP concentrations were both only in the ‘Very High’ classification, but the relative water levels were not recorded so this cannot be put into context.

Whatever the case, the situation for the health of these Conservation Category Wetlands is not good with either similar or worse conditions still apparent.

Figure 6 – Inundation at 1.60m AHD

Figure 7 – Inundation at 1.20m AHD

Conclusion

The health of the Serpentine Wetlands has been largely impacted by the ‘efficient’ drainage system that limits any water storage capacity; the situation being exacerbated by the changes in rainfall due to Climate Change.

A critical part of the assessment process documented here is to review the change in vegetation health that has occurred in the Project Area since the “Spring Flora and Vegetation Survey” was undertaken by Emerge Associates in 2016. That should guide what is needed to improve wetlands and vegetation health with respect to proposing any hydrological changes and provide recommendations to DBCA to assess and approve.

With the data now being recorded, it should be possible to model alternative drainage options and adjust the outlet level to potentially hold a limited amount of water back to help the wetlands return to health and that will also assist the health of the TEC’s located in the floodplain above the wetlands. This work to assess the current health of the vegetation both in the catchment and wetlands is is part of the Australian Government’s Urban Rivers and Catchments Program funding.

Further Information

Climate adaptation? Creating Rivers from drains; Saving our wetland’s flora and fauna

This project is funded by the Australian Government’s Natural Heritage Trust under the Urban Rivers and Catchments Program, with the support of the PHCC and the Western Australian Department of Water and Environmental Regulation.